By Lady Houston

FROM WIKIPEDIA COMMONS

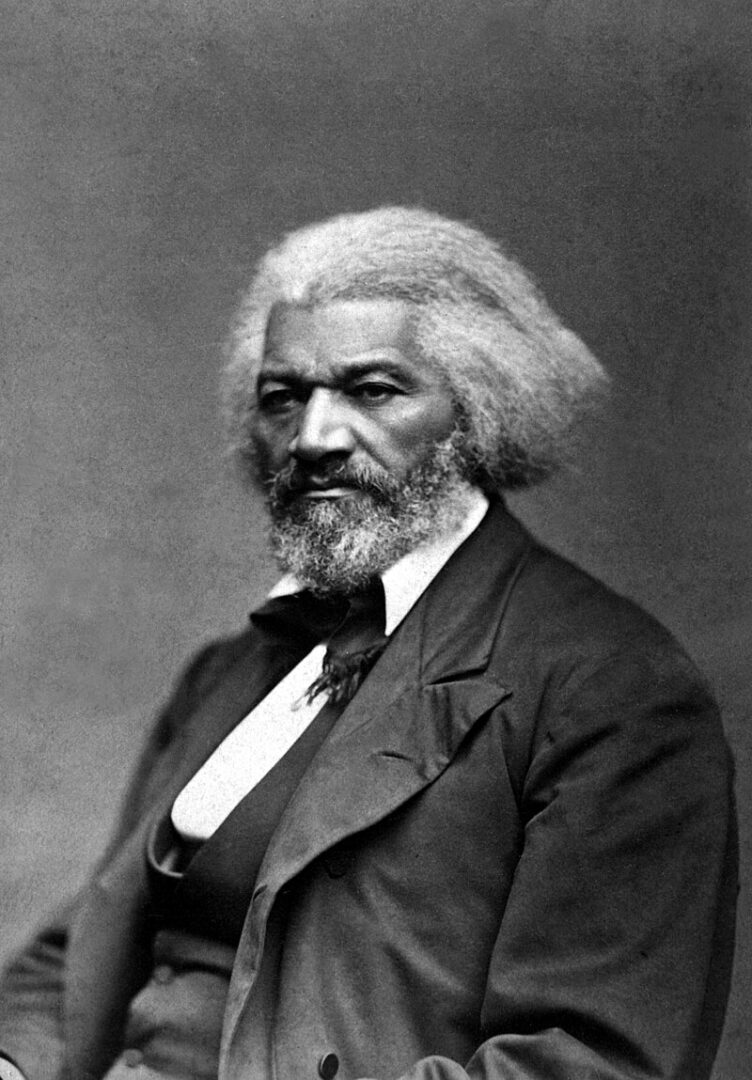

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, c. February 1817 or February 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. He became the most important leader of the movement for African-American civil rights in the 19th century.

After escaping from slavery in Maryland, Douglass became a national leader of the abolitionist movement in Massachusetts and New York, during which he gained fame for his oratory and incisive antislavery writings. Accordingly, he was described by abolitionists in his time as a living counterexample to enslavers’ arguments that enslaved people lacked the intellectual capacity to function as independent American citizens Northerners at the time found it hard to believe that such a great orator had once been enslaved. It was in response to this disbelief that Douglass wrote his first autobiography.

Douglass wrote three autobiographies, describing his experiences as an enslaved person in his Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845), which became a bestseller and was influential in promoting the cause of abolition, as was his second book, My Bondage and My Freedom (1855). Following the Civil War, Douglass was an active campaigner for the rights of freed slaves and wrote his last autobiography, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. First published in 1881 and revised in 1892, three years before his death, the book covers his life up to those dates. Douglass also actively supported women’s suffrage, and he held several public offices. Without his knowledge or consent, Douglass became the first African American nominated for vice president of the United States, as the running mate of Victoria Woodhull on the Equal Rights Party ticket.

Douglass believed in dialogue and in making alliances across racial and ideological divides, as well as, after breaking with William Lloyd Garrison, in the anti-slavery interpretation of the U.S. Constitution. When radical abolitionists, under the motto “No Union with Slaveholders”, criticized Douglass’s willingness to engage in dialogue with slave owners, he replied: “I would unite with anybody to do right and with nobody to do wrong.”